Award-winning article on how to stick with commitments and your new goals.

A new word recently brought to mind an old phrase.

The old phrase? One we've all used, "I'll get around to it someday." Some clever person obviously recognized the opportunity for a humorous wordplay, creating a wooden coin emblazoned with "Round Tuit" on the front – and then carried them to give to anyone uttering that phrase. "Here, have this. See? You just got a Round Tuit."

The new word? "Akrasia." I subscribe to Nancy Friedman's outstanding blog, Fritinancy, which recently had a fascinating post, "Word of the Week: Akrasia." Nancy's opening provides an excellent summary of the concept and the word's origin:

Akrasia: A lack of command over oneself; a weakness of will. Akrasia encompasses procrastination, lack of self-control, lack of follow-through, and any kind of addictive behavior. (Source: Daniel Reeves, an economist who blogs at Messy Matters.) Pronounced ah-CRAZE-yah.

Akrasia was coined in ancient Greece from words meaning "lack of" and "power"; the word was used by Plato, Aristotle, and other philosophers to describe a paradoxical

inability to act in one's own interests.

Later in the post, Nancy explains the concept of a "commitment device" – a means to commit yourself to a particular course of action – and then provides links to two web sites, Beeminder and stickK, allowing users to formulate and enforce a "commitment contract."

Fascinated with "akrasia"– both the word itself and the underlying concept – I went to the two sites to learn more. For both sites, the "means to commit yourself" – defined in a commitment contract you write – is some sort of negative consequence to be avoided. For Beeminder, the only negative consequence available is money – and its formula penalizing you for "failure to stay on track" becomes more and more steep, increasing each time you get off track. In contrast, stickK allows you to specify your own negative consequences, or skip them entirely.

The Beeminder site has an associated blog, and one of its earliest entries, How To Do What You Want: Akrasia and Self-Binding, written by Daniel Reeves, explains akrasia, self-binding, and commitment devices, and provides links to other resources.

While this blog post was helpful, I also looked at a more scholarly article on these topics referenced by Nancy Friedman's blog post, an April 25, 2010 paper, Commitment Devices, authored by three professors at Yale University (one of whom is a co-founder of stickK).

Both the Beeminder blog post and the scholarly article were helpful in explaining the concepts, yet both were hard to follow, for various reasons. What follows are some terms and examples drawn from these two sources, with my simplifications and clarifications – and also with my own extensions to, and examples of, the concepts.

Breaking It Down ...

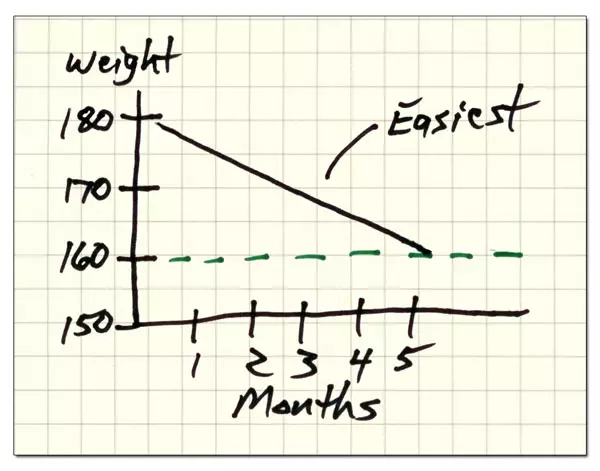

Let's take a simple example and work it through. Say you weigh 180 pounds and you'd like to get down to 160 pounds, which would be a healthy weight for you. You'll need to lose 20 pounds, and your doctor has advised you to lose no more than 1 pound per week – following this advice, you'll need 5 months to meet your goal.

Let's assume you've also read or heard Patti Digh's excellent advice in Four Word Self Help: Simple Wisdom for Complex Lives, "Eat less, move more." (This book was included in my June 2011 book reviews.) If you're always fully rational, you'll devise a diet and exercise regimen to lose, on average, 1 pound per week – and then you'll stick to it.

You start out, with every intention of easily meeting your goal. Graphically, this looks like this:

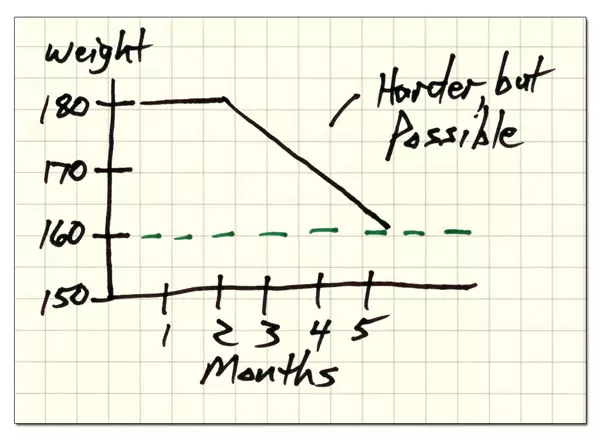

And then what happens? Akrasia kicks in. You sleep in and skip the gym, or you mindlessly munch junk food while watching TV. You say "I'll get around to it – next week." And then a few weeks go by and things look like this:

Now, to meet your goal of 160 pounds, you'll need to lose 2 pounds a week – this is more than your doctor suggested, but let's assume this is still a safe level of weight loss. Losing 2 pounds a week is harder to achieve than 1 pound weekly, but it is still possible.

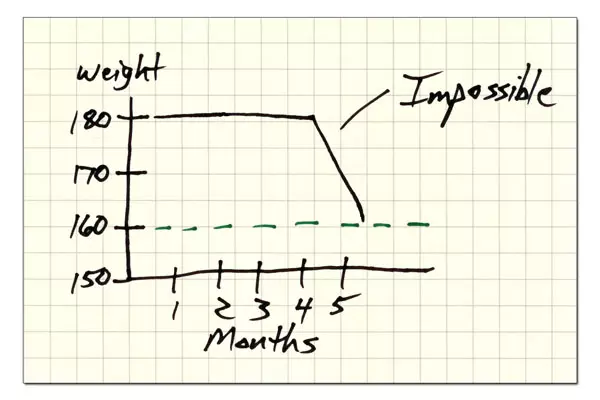

And then what happens? Once more, procrastination – you'll get around to it next week ... for 6 more weeks. Now you're only left with one month to reach 160 pounds:

To meet your goal, you'll need to lose 20 pounds in one month – and this is likely not only impossible, but your doctor would probably say it is unhealthy, too.

... And Finding Short-Term Trumps Long-Term ...

The cause of all this? Your "Long Run Self" and your "Short Run Self" have tangled with each other, and your Long Run Self came up ... short. Your Long Run Self handles your planning, looking forward to the long-term. Your Short Run Self handles your doing, with near-sighted focus on the short-term.

Similar to a financial analysis discounting cash inflows and outflows to reflect passage of time, our minds discount costs and benefits when we analyze a situation – we over-weight the immediate results and under-weight future results.

- We over-weight the short-term reward of watching TV and snacking, as well as the short-term discomfort of exercising and dieting.

- We under-weight the long-term benefit of a healthy weight, and also the long-term problem of being overweight.

Because we over-weight the short-term, our Short Run Self wins out because there are immediate short-term benefits – receiving a positive consequence (watching TV) and avoiding self-discipline (an exercise and diet regimen) – weighted more heavily than the long-term benefit.

To address akrasia, we need to reduce the short-term benefits – or increase the short-term costs. How? Change the weighting of costs and benefits by binding ourselves to a commitment device, then provide incentives – specifically, negative consequences – to more than offset the short-term benefits.

- Why negative consequences? Remember, akrasia occurs when we let short-term positive consequences outweigh long-term negative consequences – so we need to add short-term negative consequences to even things up.

- How negative do the consequences have to be? As much as is needed to make you choose to incur the short-term discomfort of exercise and diet over the negative consequences, yet not so negative to make you unwilling to freely choose to limit your actions – self-bind – by using a commitment device.

A practical way to assess whether you've added enough negative consequences to influence your behavior, yet not so much to turn you off? What I call the "Think-Gulp-Yes Test" – when you consider self-binding to a commitment device that causes you to think carefully about it, swallow hard, and then say "yes" to actually do it.

... Until a Commitment Device is Used

The Yale professors' definition of "commitment device" is, with some simplification, "an arrangement entered into by an individual with the aim of helping fulfill a plan for future behavior that would otherwise be difficult because of, for example, lack of self-control." The authors also define:

- Hard Commitments – Real economic consequences, with penalties for failure or rewards for success.

- Soft Commitments – Psychological consequences for failure or success.

The professors describe a commitment contract as "a commitment device that is an actual contract between two parties, rather than a unilateral arrangement employed by an individual to restrict his or her own choices." Later in the article, they note that a "commitment contract must weigh the need for commitment against [a person's] wish for flexibility." If the flexibility is based on observable or verifiable conditions, either specified at the time of the contract or obviously using common sense, then the commitment contract can still be effective.

- Being sick or having a family emergency are conditions which can be observed or verified, and are certainly reasonable – thus, flexibility is appropriate.

- Having a "hard" workweek is difficult to assess because "hard" is subject to interpretation.

- If a "hard" workweek is defined, upfront, as working 60 or more hours in a week, then this condition is verifiable, and is certainly a valid reason to be flexible. Should the person work 60 or more hours in a week, then flexibility is appropriate and the contract can still be effective.

- Failing to specify, in advance, what constitutes "hard" makes assessing a request for flexibility more judgmental, potentially making the contract ineffective.

Stated another way – a commitment device is some mechanism to curtail options available to our short-run self, for the ultimate benefit of our long-run self. It stops immediate gratification and forces delayed gratification. It makes follow-through real and precludes "weaseling out." A commitment contract is a special type of commitment device – you enter into a contract to allow someone else to monitor and evaluate your choices, and enforce agreed-upon consequences as needed.

Examples of Commitment Devices ...

The Beeminder blog mentions many types of commitment devices – here are a few:

- Traveling somewhere to do a task you could do – but won't do – at home, to escape distractions you lack the willpower to ignore.

- Putting money in a Christmas Club account – a savings account prohibiting withdrawal until December.

- Preferring gift certificates instead of cash, to ensure you'll use it towards the intended purpose.

- Preferring coupons or gift certificates with expiration dates to ensure you'll eventually get around to using them.

- Using MasterCard's inControl credit card that shuts off once a set budget is reached.

- Taking a diet pill that causes diarrhea when you eat too much fat.

- Taking Antabuse to cause yourself to get sick if you consume alcohol.

I've ordered the examples starting with the ones I'm most likely to do and ending with ones I'm least likely to do – in other words, I've ordered them by my increasing resistance to the negative consequences. Would I ever do one of the two last? Not unless I had a major problem and needed to quickly turn things around.

For the last two examples, the blog's author, Daniel Reeves, comments "They seem psychologically very similar to setting up a commitment contract with a large cash penalty."

... And Commitment Contracts With "Hard Commitments" ...

Remember, a commitment contract is a special type of commitment device – one which you enter into with another person. Both stickK and Beeminder web sites establish commitment contracts between you and the site:

- stickK tracks all types of goals, and money is an optional stake. If you put money at stake, it is a constant amount of your choosing per reporting period – the money is turned over to a charity, anti-charity (a group you detest), or a "friend or foe" (an individual) of your choice at the end of your contract. stickK also optionally lets you specify a referee (a person to monitor your progress and verify your reports) and supporters (friends to encourage your progress).

- Beeminder only tracks numeric goals, and its only stakes is money. If you choose to use money as stakes (you can specify $0 as your stakes), you turn over to Beeminder an escalating amount of money for each violation of your contract. Beeminder does not currently let you specify a referee or supporters.

These contracts are centered around "hard commitments" – economic penalties are involved. Daniel Reeves, the author of the Beeminder blog post, says "I'm partial to money myself but I don't claim it's the only way. Still, many obvious alternatives – like harnessing social disapproval – can fail if implemented naively." How might social disapproval – shame – be useful? Can a contract with a "soft commitment" – a psychological consequence – be effective?

... And Ones With "Soft Commitments" Including "Todd's Results" ...

I have previously written about several things I learned from a remarkable presentation by Henry Cloud. He used a personal example – how he completed his doctoral dissertation – to illustrate his points. He had put off getting started on this major task because he was overwhelmed just thinking about it. Then he observed ants in an ant farm building a city – a seemingly impossible task, until he realized it was accomplished by moving one grain of sand at a time. So he devised an external structure to help him get things done – he entered into a commitment contract with an accountability partner:

- The commitment – He would call his accountability partner at a designated time every Monday morning, unless he was ill. During the call, he would report progress against the prior week's goal, and then set a new goal for the upcoming week.

- The negative consequence – He would give his favorite pen – a Mont Blanc pen that was a gift from a friend – to his accountability partner if he failed to call him at the designated time every Monday morning, or failed to meet his goal.

While this commitment and negative consequence seem trivial, they were effective – for two years, he always met his goals, even if that meant staying up late Sunday night to be ready for the Monday morning call. At the end of two years, he had completed his dissertation.

Dr. Cloud's arrangement was a "hard commitment" because it involved an economic penalty – the loss of an expensive pen – yet the contract also had a "soft commitment" since the pen had sentimental value. Which was more effective, the hard or soft commitment? Dr. Cloud never said, yet I bet it was the soft one – if he lost the pen from his friend, he could certainly buy another pen ... but not the one given by his friend.

I have my own arrangement for achieving goals called "Todd's Results." While this is a "soft commitment" because the negative consequences are psychological – a temporary loss of my BlackBerry and a permanent red "X" on my web site – these consequences have been more than sufficiently negative to ensure I have always – at least through the time I write this – met my monthly goals. Of course, my accountability partners understand unexpected events inevitably occur and allow for appropriate flexibility in the goals, as long as I inform them of the events and I request only a reasonable amount of flexibility.

... And the New "Todd's Accountability Challenge"!

A friend, Jillian Gibson, recently had her own case of akrasia, so I invited her to do what I do to overcome a "round tuit" and commit to – and publish – her goal and interim results permanently on my web site. She thought about it, swallowed hard, and said, "Yes, I'm up to the challenge. Let's do it!"

Jillian is the first person to accept "Todd's Accountability Challenge" – an experiment in applying personal accountability. She is currently planning to formally undertake the challenge in May 2012 and commit to meet her goal for three straight months.

Even though my accountability challenge has only a psychological consequence, it provides a short-term negative consequence to – hopefully – counter the short-term benefits of putting off something, without being so negative to scare someone away. In Jillian's case, it passed her "Think-Gulp-Yes Test." In her mental calculus, the balance in my challenge must have been about right – it apparently provided enough negative consequence to bring her Short Run Self to heel, while not being so off-putting as to cause her to say "No" and deliver a benefit to her Long Run Self.

Are You Up to the Challenge?

So, how about you? Has your Short Run Self been bullying your Long Run Self? Do you have a lingering "To Do" you'd finally like to make "Done"? Would committing to publish your goal and results permanently on my web site be sufficient motivation for you? Does this challenge pass your "Think-Gulp-Yes Test"?

If you'd like to accept to "Todd's Accountability Challenge," just let me know. My hope is to start one new person on this every month, building up to several people being at various points in the process for a particular month. Think of it as an opportunity to get a "Round Tuit" and take a little akrasia out of your life.

Todd L. Herman